This past weekend I was asked to be on a podcast that’s a little outside my usual scene.

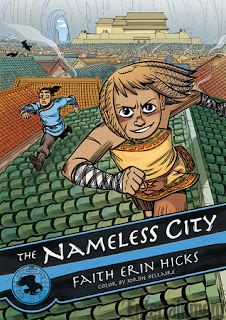

I go to an art club called Drink and Draw every month, and many of the people there are more “serious” artists than I am (or at least more talented). Anyway, my friend Eric is the club’s host, and he usually picks me up on his way there so we talk about stuff. This time, we ended up talking about the comic book The Nameless City by Faith Erin Hicks, which I hadn’t read.

It turned out that Eric had seen a Twitter discussion about whether The Nameless City was appropriative, because it has a cast and setting clearly based on ancient China, but it’s written by a white woman. An Asian artist on Twitter was saying books like this and television shows like Avatar: The Last Airbender (which clearly influenced Hicks) are disappointing in a way because it feels like mainstream culture is capitalizing on “diversity” while still not making way for people to make art about themselves.

This is a good point, and Eric and I had a spirited discussion about it. He invited me to come on his podcast the next day to talk about the same thing with his friend Robbie (who I also know but he’s mainly just an acquaintance of mine–we hang out with the same people and he’s been in my house but we don’t really talk much). Of course, first I had to read the book. So I read it at Drink and Draw before doing my art.

The podcast episode I was on is here: Handsome Boys #142.

A review I did of the book is here: The Nameless City by Faith Erin Hicks (review).

Here’s the thing: We all know we would like more diversity of all kinds in fiction, and we all know the only way it can happen is if people make it on purpose. The problems are many, though, and one of the most insidious is that mainstream audiences often think a piece of media is not “for them” if it primarily contains people who are not like them. When we “mark” a piece of media, usually the people who are described by that mark will flock to read it, but it will remain less circulated, undervalued, probably written off as niche, and rarely reaching the broader world. But if the mainstream media actively solicits media featuring characters, settings, and messages less commonly featured, will that help?

Some say it’s really not going to help that much if the creators filtering the message into the mainstream are not telling their own stories. If they’re telling underrepresented populations’ stories through their own lenses, does it really serve the purpose of bringing those stories to light, or is it just people from the mainstream culture wanting to pat themselves on the back for being so inclusive now that diversity is a buzzword?

So what do the underrepresented populations in question have to say about this? Well, as usual, it’s a mixed bag. Some want to know why mainstream authors with plenty of connections want to hijack their narratives and give them to the outside world so they can gawk. Some want to know why they’re not being solicited to contribute work if it’s their perspective that’s supposedly so valuable. And some believe one of the things that actually does help pave the road for that to happen is getting mainstream audiences to understand that work about “the other” can be for them.

Avatar: The Last Airbender managed to get a cartoon onto mainstream television that did not contain a single solitary white person, and it’s definitely got a large cast, too. The names and concepts definitely have Asian inspiration of various sorts, but it is still Fantasy Asia, so the creators get a bit of a pass if something isn’t “accurate.” And its creators are two white guys. They have a ton of Asian consultants and people working on the show, but it’s still a mainstream Nickelodeon show by Mike and Bryan. Perhaps this sends a message to big media companies that audiences can and do accept and enjoy these stories. Will this prompt them to actively solicit shows with actual Asian creators at the helm? Too early to tell.

But it’s clear from most of the dialogue that underrepresented people do not want to build a fence and say “you should not write about us.” There’s a very good reason why those folks are wary of mainstream creators (why do they want to do it? what are they going to screw up?), and they also have good reason to expect well-meaning mainstream creators to do their research extensively. That research can include bringing in test audiences from the population they’re trying to portray, including creators from that background as co-creators or permanent contributors, and consuming media and commentary by those populations.

I want men to be able to write about women, for instance–and I want men who are making creative works about women to help combat the notion that works about us are marked for only our consumption, irrelevant to people who aren’t women–but I’m not going to appreciate it if the way the male creator makes his woman character feel “authentic” is to graft in his assumptions about what women think about. I have seen a male author praised extensively for wow it’s so hard to believe a man wrote this book about a woman, it feels so feminine but I was shocked that the supposed authenticity was literally her worrying about being fat and being obsessed with shoes. I also once read a very popular male author’s book that was from a teenage girl’s point of view and I cringed every time he tried to make her say/do something that reminded us of her gender (“ugh why do boys make us watch their movies? we’re not interested lol because ladies!”). I would ask these men to read books that are by women, to try to understand why we write what we write, and then don’t appoint yourself to tell a Feminine Story About Being Female. You don’t need to tell that story, but yes, please, put female characters in your book.

From a practical standpoint, I think it’s very important for mainstream audiences to start seeing people who are different from them in their everyday media. Without having to deliberately seek it out. Because people who aren’t like you are part of your world. Most media does not currently reflect that. We also need both “issue books” and “incidentally representative books.” The Nameless City was not about what it is to be any of the Asian populations it included, though it gave its own culture to the fantasy world (as it should). So it’s a nice thing if people from all backgrounds can go into a bookstore and see this and think “hmm that looks interesting” rather than thinking “welp, Asians on the front, must be some kind of niche media.”

I remember working at a bookstore and having a woman pestering me to make recommendations for “good books” and rejecting all the suggestions before I could even finish a sentence, and one of those attempts was me saying “You might like Life of Pi. It’s about a boy from India–” “NO.” She immediately wasn’t interested as soon as I said “India.” We also had an “African-American Fiction” section when I first started at the store. Many black readers would come in asking for the section, and other readers were scandalized by its existence–I heard black readers say it was gross to segregate it from the “regular” fiction, and I also heard non-black readers snot about it wanting to know where the white fiction was. (Clue phone: Pretty much the entire rest of the store.) Later it was integrated (along with several other categories) into one big mega-fiction section. Some people said that was the right choice. Some people were frustrated that they could no longer easily browse a section that was for them, and interpreted it as an attempt to take the entire thing away. Both sides are kind of right, but I think I’m personally more invested in my background and other people’s backgrounds all being presented as “for” anyone to be exposed to.

And here’s something interesting.

Wait, what’s that? Is it a children’s book with a same-sex couple on the front? Yeah it is.

This book is coming out later this year. It’s explicitly described in the book summary as a love story–depicted in the comfortable fairy-tale style children are used to seeing in all their other storybooks. There is no sticker on it proclaiming “LOOK, IT’S LESBIANS!!” or anything, but even though some people might interpret the red character as a boy because of how she’s dressed, a basic glance at the information will make it clear that their names are both feminine-coded names (Sapphire and Ruby) and they both use “she” pronouns. They’re in a clear casually intimate pose on the front cover. This is not being designated as a Special Interest book. It’s just going to be released as a storybook. For the regular storybooks section.

Recently in an interview, creator Rebecca Sugar said this about children’s media:

I think if you wait to tell kids, to tell queer youth that it matters how they feel or that they are even a person, then it’s going to be too late!

You have to talk about it–you have to let it be what it gets to be for everyone. I mean, like, I think about, a lot of times I think about sort of fairy tales and Disney movies and the way that love is something that is ALWAYS discussed with children. And I think also there’s this idea that’s like, oh, we should represent, you know, queer characters that are adults, because there are adults that are queer, and you should know that’s something that is happening in the adult world, but that’s not how those films or those stories are told to children. You’re told that YOU should dream about love, about this fulfilling love that YOU’RE going to have. […]

The Prince and Snow White are not like someone’s PARENTS. They’re something you want to be, that you are sort of dreaming of a future where you will find happiness. Why shouldn’t everyone have that? It’s really absurd to think that everyone shouldn’t get to have that!

Based on Rebecca Sugar’s history, it’s clear that she is very invested in portraying same-sex couples as natural, as an everyday part of life, as not worth batting an eyelash at in protest. She tends not to make her works “issue” works, and on her television show she’s included a large cast of non-white characters (as well as coding some of her aliens as having features typically associated with people of color), and she just presents that and lets it be without pointing at it and saying “look what I did.”

Rebecca’s romantic partner (and major contributor to her show) is Ian Jones-Quartey, who is a black man, and most of the voice cast and many of the writers are also people of color. But this is not written as a niche show. Rebecca Sugar hasn’t publicly identified as any stripe of queer as of this writing, and she’s partnered with a man, though I know better than to say that means we know anything–and ethnicity-wise she looks white, but she has demonstrated over and over that she believes racial diversity and queer representation belong in mainstream media, even for–ESPECIALLY for–children. Because, as she said above in the quote, we should all grow up knowing we can have that. That we’re people. That we don’t have to wait until our minds have formed around us being “other” before we’re gently coaxed “back” into society. In the interview, she also said some vague things about how she never watched Disney movies thinking that could be her, though I don’t know in what ways she was unable to relate. But I can certainly say I would have grown up feeling more like the world wasn’t someone else’s place I was just trying to live in if the media I consumed in my youth had hinted that people like me were real.

Now I’ve heard tell that Seanan McGuire has written a book with an asexual protagonist. (The book also contains a trans man who is, I believe, a romantic interest.) The author is bisexual (and as far as I know not asexual-spectrum), and this is one of the only novels out there that has not just an asexual character tucked in someone’s pocket somewhere but an asexual protagonist. This is also not a book about the character realizing she’s asexual, nor have I heard that it heavily features that revelation. It just is. As it should be. The question is, did she do it right?

I’ll have to see, by reading it. And even though I’m an asexual woman, obviously I’m not the decision-maker on whether Seanan McGuire has written an asexual character “wrong.” I would certainly be able to read it and say “I wish that hadn’t been there” or “I wish that had been phrased differently” or “just once I’d like to see an asexual character who isn’t also XYZ.” (I withhold judgment until I read it, obviously.) But I must admit that as an asexual woman knowing a bisexual author has included a character of my incredibly underrepresented background, my first thought was “ohhhhh jeez I hope it isn’t terrible.” I feel bad that this was my first thought, because though I’m passably familiar with Seanan McGuire, I’ve never read any of her long fiction. I have no reason not to trust her, and I trust her more than I’d trust a straight person to write aces. And yet that was my knee-jerk reaction. Because I’m used to mainstream fiction taking people I can relate to and framing them as broken, as cold or confused, as villainous, or as needing to learn more about being human. And it isn’t just hurtful to see yourself represented poorly in a story. It’s hurtful to know this is a mainstream presentation and other people are going to be even more likely to think about me that way. I’ve been taught to expect this when non-asexual people try to show the world who I am.

Right now we don’t have enough characters like us in the media to risk getting a large percentage of them wrong. Just like a straight white male character being an utter douchebag in a movie will not make people think differently about straight white men, there does need to be room for non-majority characters to not be perfect people, but since people are establishing lasting impressions of us based on how media portrays us, we need to ask creators to be sensitive to this when they plan their presentation. If you have no exposure to a group but you see them on TV, you generalize–even if someone else has chosen how that group is portrayed without being part of it. We cannot realistically arrange global exposure to every marginalized group, but we can be responsible with how that exposure comes through our media.